The majority of the casebooks are in Forman’s and Napier’s hands, but it is important to spot where someone else — an assistant, associate, or client — has left their mark on the page too. In the edition, we designate hands with initials (e.g. ‘RN’ for Richard Napier), and they are gathered together in the ‘Hands’ facet. The scribe is often the practitioner or a co-practitioner.

In Forman’s casebooks, Napier’s hand features in twenty-one cases, and a pair of unidentified scribes are represented in more than a hundred cases each. Notes from two women patients — Lucy Balle and Dorothy Bruarton — are also preserved in Forman’s cases.

In Napier’s casebooks, Forman’s hand appears in forty entries, with Napier’s known associates — Gerence James, Napier’s nephew Sir Richard Napier, Robert Wallis, Ralph Ruddle, Theodoricus Gravius, and Mr Willoughby — making frequent interventions. A further eight scribes remain unidentified, most with only a dozen instances.

This page describes the hands in the casebooks. These were working documents, not fair copies, and the script is often messy. Good introductions to palaeography, (the study of old handwriting), with online tutorials and guidance on deciphering Elizabethan secretary hands, are Cambridge University’s online course on English Handwriting 1500–1700 and the National Archives’ online palaeography tutorial.

Dr Simon Forman

Simon Forman’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 219, f. 190r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

The vast majority of Forman’s entries are written in his own hand. Forman writes in a typical Elizabethan secretary hand, with some italic features. Perhaps echoing medieval practices, he sometimes writes initial letters or whole names in much larger script, occasionally using red ink. He often uses enlarged lower-case letters rather than upper-case forms.

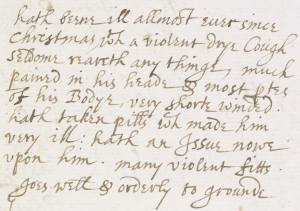

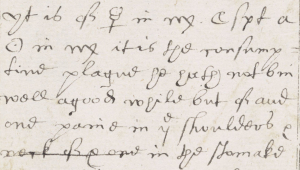

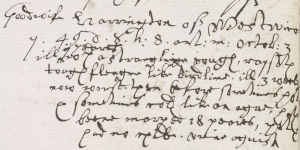

Mr Richard Napier [Sandy][Richard Napier [Senior]]

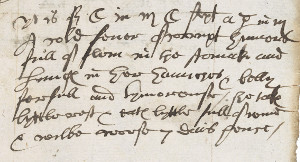

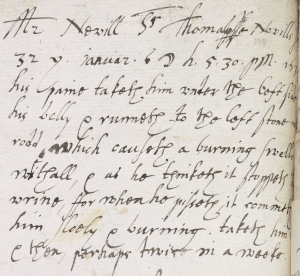

Richard Napier’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 228, f. 204. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Richard Napier also writes in a typical late Elizabethan secretary hand, with more italic features, and his script is notoriously slovenly. Most of the content of his casebooks is written in his hand. See our letter guide for help to read it.

Mr William Bredon

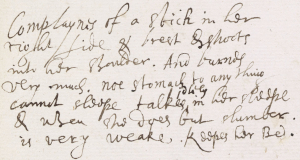

William Bredon’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 240, f. 79r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

The rector of Thornton in Buckinghamshire from at least 1616 until at least 1636, Bredon corresponded with Napier on astrological matters, consulted him at least twice (in 1617 and 1618), and supplied Napier several times with natal charts at Napier’s request during the later 1620s. The figure and the text below it on CASE67406 are in Bredon’s impressively neat italic hand. For examples of his typical hand see various letters to Napier: NOTE882, NOTE883, NOTE884, NOTE885; for examples of astrological figures drawn by him see NOTE878, CASE79995, and , each of which also has associated notes in his italic hand; for a more extensive example of his italic hand see .

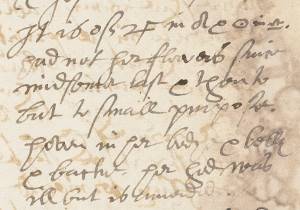

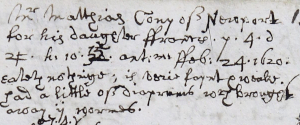

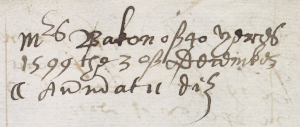

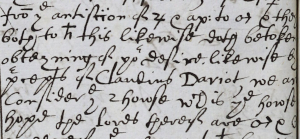

Mr Theodoricus Gravius

Theodoricus Gravius’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 412, f. 65v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Napier’s assistant towards the end of Napier’s life. Samples of his hand (as identified by William Black) can be seen in NOTE10187 and in neat form in NOTE10198; and judging from the overlined ‘Mr’ with the 2-shaped r, as well as the general shape of the writing, it also appears in the question sections of the entries CASE78515, CASE78518, CASE78519 and CASE78521. He also has a less neat hand that appears in several entries and notes; this is visible, below his neater hand, in CASE74844. A few of his notable habits are: in dates he tends to use numeral abbreviations for his months, such as ‘9bris’ for ‘Novembris’ and ‘xbris’ for ‘Decembris’. When he writes ‘p M’ or ‘p Mer’, he typically uses a lower-case ‘p’ and an upper-case ‘M’. When writing Latin he marks instances of the letter ‘u’ with an accent to distinguish them from the letter ‘n’ (though they are distinguishable on the basis of shape anyway). His Scorpio symbol (♏) is very different from the other scribes’, with the tail of the scorpion resembling a curl rather than an arrow.

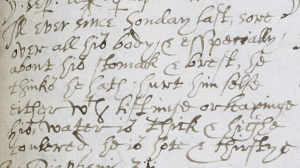

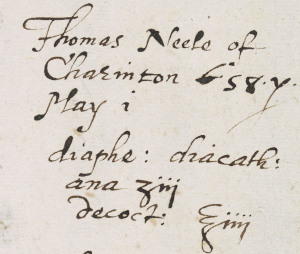

Mr Gerence James [Marks]

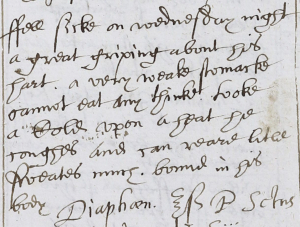

Gerence James’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 207, f. 53r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Napier’s curate (sometimes referred to as ‘Mr Gerenc(e)’) wrote more than 3,000 entries in Napier’s casebooks. His hand is superficially similar to Napier’s earlier, neater hand, but fussier; he records times in the style ‘ho. 1. 45. a m.’; cf. Forman’s ‘45 p 1 an’ m’’ and Napier’s ‘hor. 1. 45. ant m’. Unlike Napier, he can spell ‘Alice’, but not ‘Elisabeth’, from which he habitually omits the ‘i’. See our letter guide for a full alphabet and set of symbols in James’s hand.

Mr Richard Napier [the nephew][Sir Richard Napier]

Sir Richard Napier’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 412, f. 150Ar. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

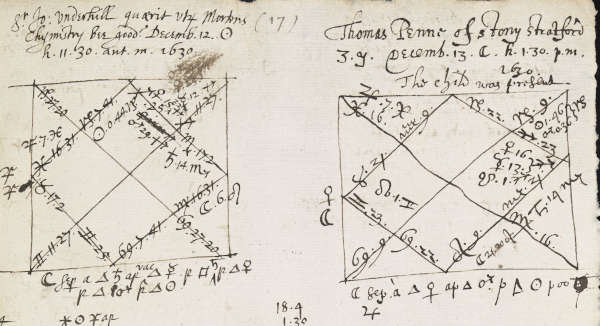

Sir Richard Napier’s hand begins to appear in the casebooks from 1629. For an example of his looser hand see CASE79743 and subsequent entries in the same volume; for an example of his neater hand see CASE71075 and other entries on that page. His hand can be difficult to distinguish from Ralph Ruddle’s, but several features usually make it possible to tell Sir Richard’s apart. (See the top half of MS Ashmole 232, p. 17 for the two hands side by side: Ruddle’s is in the top left of the page (CASE71093); Sir Richard Napier has written the entry in the top right (CASE71095), and large parts of the other two entries on the page.)

The handwriting of Ralph Ruddle and Sir Richard Napier, side by side. MS Ashmole 232, p. 17. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Mr Ralph Ruddle

Ralph Ruddle’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 232, p. 256. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Napier’s curate from some time around late 1624 until Napier’s death in 1634, Ruddle first writes in the casebooks on 21 December 1624 (see CASE59555), but otherwise his hand occurs c. 1629–1634. It can be identified as Ruddle’s by comparing it to entries in the parish register of Stoke Dry, Rutland, from the period during which he was rector (up to his death in 1689). The pages of the parish register are signed by him.

Ruddle’s hand is similar to the neater form of Sir Richard Napier’s, but less rounded, and there are differences that usually make it possible to tell them apart: Ruddle writes ‘L’s whose ascenders are kinked; he always, or almost always, uses epsilon-shaped ‘e’s; his ‘h’s are italic and do not drop below the line (unlike Sir Richard’s). When giving times in the morning he sometimes writes ‘a. m.’ and sometimes ‘ant. m.’. When he writes ‘p m’, usually (though not quite always) the loop on the ‘p’ is not quite closed, and ends with a short but noticeable horizontal stroke (as in CASE71081 or CASE22488 and CASE22490). His Cancer symbols (♋) are typically horizontal, like two tadpoles swimming past each other, whereas both Napiers write their Cancer symbols like the number 69. For a useful side-by-side view of the hands of Ralph Ruddle and Sir Richard Napier, see the top half of MS Ashmole 232, p. 17, reproduced above in the discussion of Sir Richard’s hand: CASE71093 (top left) is Ruddle’s; CASE71095 (top right), and large parts of the other two entries on the page, are by Sir Richard Napier.

Mr Robert Wallis

Robert Wallis’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 213, f. 137r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Napier’s curate 1612–1616 and after that an occasional visitor to Great Linford; his hand appears intermittently in the casebooks from at least 1615 on. Charts produced by Wallis are typically drawn differently from Napier’s: where in Napier’s charts the diagonal lines drawn from corner to corner meet in a cross (×) at the centre, in Wallis’s charts a blank square is normally drawn at the centre. See for example CASE42728. Wallis sometimes writes calculations for his charts so that the ‘sidereal noon’ is the second item listed, rather than the first (as almost all the other practitioners and scribes do). His Saturn symbols are curious and angular (there is an example at CASE42728) and very distinctive.

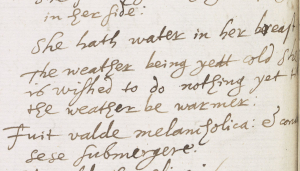

Mr Willoughby

Mr Willoughby’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 193, f. 189r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

A practitioner who stood in for Napier during some periods of Napier’s absence; his hand appears initially in August 1605, then for extended periods during the springs of 1607 and 1608 and the summers of 1612 and 1614. He writes e.g. ‘y. 30’ rather than ‘30 y’ and capitalises ‘A. M.’ (or ‘Ant. M.’) and ‘P. M.’ (or ‘Post M.’). He writes his moon symbols with the convex side facing East, i.e. back-to-front as compared to Napier’s and James’s form. Like Napier, he habitually omits the ‘i’ from ‘Alice’. He is inordinately fond of full stops, which in his entries sometimes occur after (and occasionally also before) every single word, numeral or symbol in the question section. When he really does mean something roughly equating to a modern full stop, he generally uses a punctuation mark consisting of three dots forming a (more or less) equilateral triangle (⸫). He normally prefaces any treatment notes with ℞, which means that this cannot in his entries be taken as a a reliable indicator of a recipe (or of angelic advice from Raphael).

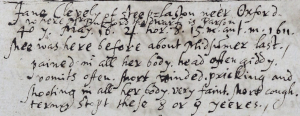

Unidentified scribe (1596–1600)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1596–1600). MS Ashmole 219, f. 206v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

This hand appears a number of times in Forman’s casebooks between the end of 1596 and the spring of 1600. The letter ‘r’ is typically written (in its medial form, at least) with sharper corners than Forman’s version. Its ‘3’s have a flat top and a sharp corner, where Forman’s are rounded. The ‘e’s are better and more consistently formed than Forman’s. Because of the small samples of this hand, it is difficult to be sure that all of the examples were genuinely produced by the same scribe; it is possible that there is more than one scribe included here with hands of similar features.

Unidentified scribe (1603)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1603). MS Ashmole 411, f. 178v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

This scribe was the copyist in whose hand we have Forman’s 1603 entries.

Unidentified scribe (1610)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1610). MS Ashmole 239, f. 19r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

The hand used in CASE24616 and CASE24617. Presumably an assistant of Napier’s.

Unidentified (1611–1612)

The handwriting of Unidentified (1611-1612). MS Ashmole 200, f. 99v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

An associate of Napier’s who on two occasions stood in for Napier in his practice. The first of his two appearances was in May 1611 (see for instance CASE38140; his second was in July 1612 (see for instance CASE40158). It is possible that this is Napier’s curate from 1610 to 1612, Thomas Stokes, but other than the timing there is no evidence of that. One notable characteristic of this scribe is a tendency to give ages in Latin (‘ætat. 50’) in passages otherwise entirely in English.

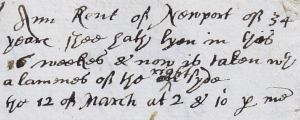

Unidentified (1622–1624)

The handwriting of Unidentified (1622-1624). MS Ashmole 413, f. 87v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

A hand that first appears on 25 June 1622, providing a few notes and calculations for a nativity (CASE54509), and last appears on 11 March 1624 (CASE57879). For an example of this hand see also CASE57737, CASE57738, CASE57739, CASE57740, and CASE57741. This is probably identical to Unidentified Hand B in Ashmole 363: note the distinctive ampersands. Like Mr Willoughby above, this scribe uses ‘℞’ more freely than Napier and it is not always safe to take it as indicating a recipe. Another feature worth looking out for is the use of ‘æ’ for ‘ætate’, before an age. The date range for this hand suggests that it may be John Miles, Napier’s curate from before March 1622 to September 1624.

Unidentified scribe (1628–1631)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1628-1631). MS Ashmole 238, f. 192v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

A hand that appears in November 1628 (see for instance CASE67402 and other entries on the same page), in November 1630 (see for instance CASE23246), and in January 1631 (CASE71259). It looks somewhat similar to Robert Wallis’s hand, and like Wallis, this scribe (in the available sample) writes his days with a ‘d’ for ‘die’, as in ‘d. ☿’. Unlike most of Wallis’s, his charts do not have a square in the centre of them (instead they resemble Forman’s and Napier’s). The Saturn symbols in this hand (see for instance the entry in the top left corner of the page at the last link) are far more normal-looking than Wallis’s.

Unidentified scribe (1628–1630)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1628-1630). MS Ashmole 407, f. 11v. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

A hand that first appears in December 1628, copying judgment given by William Bredon, then again in February 1630 writing a question out, and in March 1630, writing the whole of an entry. This scribe may be the same as Unidentified scribe (1603), the person who copied out Forman’s 1603 entries, though Unidentified scribe (1603) uses an italic ‘h’ at the beginnings of words more often than this scribe does.

Unidentified scribe (1629–1631)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1629-1631). MS Ashmole 194, p. 129. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

This hand is responsible or part-responsible for a handful of entries in Napier’s practice between May 1629 (CASE68454, CASE68455 and CASE68456) and early March 1631 (CASE71455). One notable rogue entry from Napier’s practice was entered in this hand in January 1630 into one of Forman’s volumes as CASE5292. A distinctive feature to look out for is this scribe’s tendency to use a when writing p m (as in ‘ me’’); another is that the charts, drawn freehand, end up with very curvy diamond shapes in the middle, unlike the rather straighter figures achieved by Napier and his other assistants.

Unidentified scribe (1633–1634)

The handwriting of Unidentified scribe (1633-1634). MS Ashmole 211, p. 422. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

A hand that appears between the autumn of 1633 (e.g. CASE78511) and the spring of 1634 (CASE78928). This scribe sometimes uses ‘ho:’ for the hour (if not ‘h’); ‘e’s are sometimes theta-shaped and sometimes epsilon-shaped. A recipe in this hand in NOTE10070 ascribes a recipe to ‘my Sister Mytten’. Since it was a sister of Richard Napier the nephew who married Thomas Mitton in 1629, that suggests that either this is a distinct form of that Richard Napier’s hand; or an assistant writing on his behalf; or, perhaps less likely, a sibling or in-law of his.

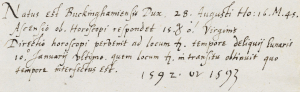

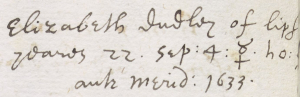

Elias Ashmole

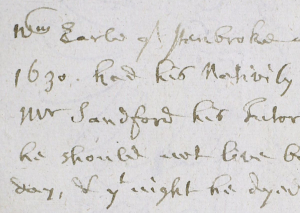

Elias Ashmole’s handwriting. MS Ashmole 174, p. 149. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2018.

Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) was an antiquary and astrologer whose impressive manuscript collection included Forman’s and Napier’s papers. A few of the items bound into the volumes of loose papers are Ashmole’s own, including several astrological charts (see for instance NOTE578 and NOTE397, and the chart and text in NOTE577). Ashmole also wrote out a note pasted into MS Ashmole 411 (NOTE304), and a multitude of brief astrological notes and calculations on the slips that he inserted as bookmarks near entries in Napier’s volumes that involved sigils.